The last few years have seen vast changes in the landscape of women’s sport:

- Professional leagues such as the WBBL, AFLW, NRLW, the W-League and Super W launched

- Landmark broadcast deals were done

- Better pay deals were negotiated for female athletes across sports like cricket, netball and football

- Female athletes like Ash Barty, Sam Kerr, Ellyse Perry, Erin Phillips and Sally Fitzgibbons became household names and role models for the next generation

In 2020, that momentum was continuing when 86,174 people crowded into the MCG to watch Australia beat India in the final of the ICC Women’s T20 World Cup on March 8th. Women’s sport in this country had arguably never been in a better position. The largest crowd for a women’s sporting event in Australia. As one Twitter user prophetically said: “Things will never be the same again after tonight”.

A week later, in response to the rapid spread of coronavirus, the Prime Minister announced restrictions on large gatherings that effectively pressed pause on sport as we know it.

Just like that, the momentum shifted…

And rightly so. Initially our biggest priorities were safety, security, health, and getting through a global pandemic.

Uncertainty was everywhere, but most definitely for women’s sport.

How would female athletes, often still juggling sporting careers with other paid work, survive financially? Would women’s sport be left behind as many sports organisations rushed to restart men’s seasons first?

For a while things looked bleak, but they are beginning to pick up again

In the last month, as restrictions are being rolled back and following the successful return of rugby league and AFL, a plethora of women’s sports have been firming up their comeback plans. Suncorp Super Netball will run a full 60-match season starting 1st August. The third season of the NRLW will start in September, with the four teams from 2019’s competition all returning. The WNBL will play a full season with a delayed start date in November. Even summer codes like cricket have now announced their international schedule.

So how do we stage a comeback for women’s sport in Australia?

Sports organisations need to double down on their investment in women’s sport

Studies produced by sports organisations like the AFL and Sport England have highlighted the economic benefits of women participating in sport, not least because of their influence on consumer purchasing decisions. The longer women participate in sport, the more likely they are to be lifelong consumers of their sports.

Australian sports organisations should take their lead from FIFA, who confirmed that their US$1 billion investment in women’s soccer for 2019-2022 will proceed despite COVID-19. Or the Japan Football Association, who recently announced the first professional women’s football league (WEL) would start in 2021. JFA president Tashima Kohzo noted that the league was about more than just football, aiming to “build a sustainable society through promoting female social participation… promoting women’s empowerment and solving social issues.”

Visibility is vital

Free-to-air broadcast has been a cornerstone of the strategies of the most successful women’s competitions in this country – AFLW, WBBL and Super Netball. As Kate Palmer said when she was CEO of Netball Australia, “Broadcast continues to be that thing that will break the back of our issues around profile”. In a year where sport broadcast deals are being scrutinised, rewritten and ultimately reduced, they will continue to be critically important for women’s sport, for the revenue but also for the eyeballs.

The balance of media coverage continues to be weighted towards men’s sport. According to a Clearinghouse for Sport report, outside major sporting events, coverage of women’s sport remains at less than 10%. This imbalance extended to sports media – at the last Olympics in Rio, approximately 80% of the accredited journalists and photographers were male. There is still much work to be done in this area to improve visibility of women’s sport.

Big events must be capitalised on

The Olympics

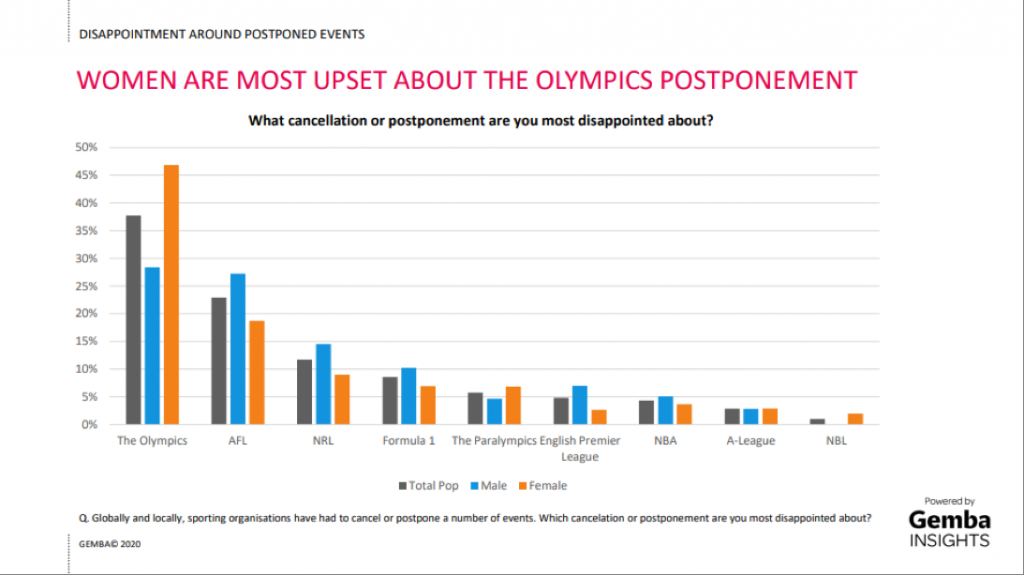

The Olympics provides a huge opportunity for all Australians to connect with female athletes. Research by Gemba earlier this year showed that Australians, and particularly women, were more disappointed about the Olympics postponement than any other sport.

Perhaps this is because the Olympics, though not yet a completely equal playing field, has fared better in terms of gender representation and equality than many individual sports. The 2016 Rio Games had the highest number and the highest percentage (45%) of female competitors ever. According to Gemba research, successful teams like the gold medal winning Women’s Rugby 7s team, are driving increased interest amongst Australians.

The Australian Olympic Committee hopes to send an equal number of male and female athletes to Tokyo, and sponsors now have an extra year to plan their activity. This provides a great opportunity to showcase Australia’s leading female athletes in equal measure to our male athletes.

FIFA Women’s World Cup

Following on from the Olympics are two big events hosted by Australia – the FIBA 2022 Women’s Basketball World Cup, and the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup. The latter, co-hosted by New Zealand, represents an incredible opportunity for women’s sport in this country. According to Gemba research, event interest for the FIFA Women’s World Cup grew 60% from 2015 to 2019. This is likely to increase further in 2023, with more countries participating than ever before and a Matildas team boasting talent like Sam Kerr and Ellie Carpenter playing on home soil.

Estimated event attendance in Australia and New Zealand is 1.5 million, with TV and digital viewership likely to be in the billions. The biggest football event ever held in Australia is estimated to bring $460m in social and economic benefits to both countries. Both Australia and New Zealand have pledged to use the World Cup to increase female representation in football governance bodies. Like any major sporting event, what is most important is that the event leaves a tangible legacy in this country, in particular on football participation. The Football Federation Australia is hoping that the event will pave the way for a 50-50 gender split in registered community players by 2027.

Action is as important as advocacy

That old adage that “you can’t be what you can’t see” continues to ring true for women in sport. Look no further than Aussie Rules for proof of what happens when young women can see what they could be. According to the AFL, in the three years since the AFLW was first announced in 2016, female grassroots participation grew by a massive 75%. Whilst increases in grassroots participation across several sports codes are being driven by more young women playing sport, it’s not just on the field where female representation is important, it’s also in the boardroom.

There are some impressive and highly-credentialled women running sports organisations in this country, like Lynne Anderson at Paralympics Australia, Marne Fechner at Netball Australia, and Jerril Rechter at Basketball Australia. But according to Sport Australia in February 2019, women represented just 22 per cent of Board Chairs and only 13 per cent of CEOs across more than 60 national sporting organisations.

The ratio needs to keep changing in all areas of sport. Intensive leadership development programs like the AIS and Sport Australia’s Executive & High Performance Coaching Programs are creating opportunities for women that will hopefully help to shift mindsets and, more importantly, behaviours in Australian sport. The previously mentioned Japanese football league (the aspirationally-named Women Empowerment League) requires 50% of staff and executives of all participating clubs to be female. These are two great examples, but we need more of these.

Those with influence need to make their voices heard

Tennis star Billie Jean King once said, “Everyone thinks women should be thrilled when we get crumbs. I want women to have the cake, the icing and the cherry on top, too.” As female athletes and industry leaders become more prevalent and visible, they need to continue to use their audiences and platforms to make their voices heard.

Ada Hegerberg, a Nike ambassador, the first person to win the Ballon d’Or Feminin, and one of the highest earners in women’s soccer, quit her national team in protest against how the Norwegian Football Federation (NFF) treats its women’s team. More recently Megan Rapinoe and the US women’s soccer team filed a gender discrimination suit (which was unsuccessful) against the United States Soccer Federation (USSF). We need the next generation of trailblazers in this country to agitate for change.

As we look towards the future and start the comeback, it’s important to recognise that the record-breaking Australian crowd in March wasn’t the result of osmosis or luck. It was the culmination of a year-long marketing campaign by Cricket Australia, that was preceded by more than a decade of building women’s cricket in this country. As far back as 2010, Australia won their first ever T20 World Cup in front of a crowd of just 8,000. A ten-year “overnight” success story.

The comeback of women’s sport will require the efforts and support of the entire industry, over a sustained period of time. As sports journalist Richard Hinds so neatly put it in an article earlier this year “The sports which find a way to cut their diminished financial cloths and stay the course with women’s leagues will be significant beneficiaries of their far-sighted approach. Those who blink will find the short-term savings come at the cost of the growth they will desperately need in an even more challenging market.” March 8th 2020 will always be a great memory, but one that we can’t let become the historical high-point of women’s sport in Australia.